When Isaac Newton first said ‘what comes up must come down’ in the sixteen hundreds we all thought we was talking about apples. But perhaps he was talking about fish?

As fishers, we rely on our ability to anticipate where fish will be. In seeking to understand where freshwater fish go and why, most of us at one time or another have probably observed native fish aggregating below waterfalls/weirs and other barriers, and worked out that certain cues trigger a desire to move upstream among many species.

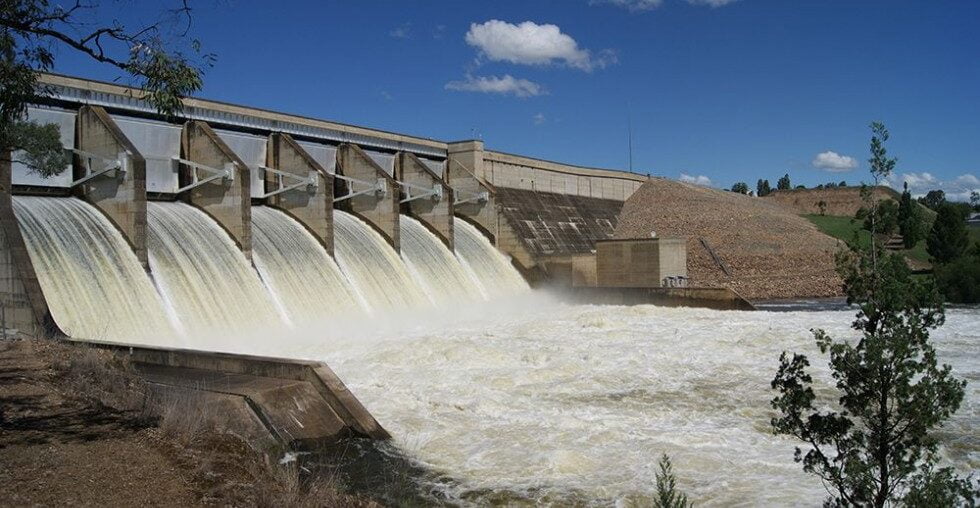

The importance of these movements is now well established for a number of our freshwater fish species, enabling them to access spawning habitat, find food, and disperse to new areas. Many millions of dollars have been invested throughout Australia to construct fishways so fish can move past barriers such as dams and weirs as they travel upstream. These fishways have proven to be fantastically effective too; up to 6000 juvenile fish were recorded moving upstream through a fishway on the Mary River in a single day. However researchers from NSW DPI are helping us to realize that we may only be addressing half of the problem, and it may be just as important that we ensure their safe passage downstream as well…

During a recent chat with Dr Craig Boys, a researcher from the NSW Department of Primary Industries, he explained,

“The issue we face is that we have created a complex system of weirs, dams, irrigation pumps and hydropower facilities to provide a consistent supply of water and electricity for our communities. And unfortunately our studies are showing that they may be impacting on native fish trying to move downstream in a number of ways”.

In the Murray-Darling Basin alone there are over 40,000 known barriers to fish movement. Many of these are what they call ‘undershot weirs’, which release water underneath steel gates as opposed to over a fixed crest. These weir designs have been shown to be particularly harmful to Golden Perch and Murray Cod: with a recent study estimating that as many as 95% of Golden Perch larvae and 52% of Murray Cod larvae are killed as they move downstream through these structures.

There are also irrigation pumps and canals along many of our rivers, and research undertaken by NSW DPI staff has shown that native fish are being sucked into them in very large numbers, and are either killed or transported into artificial water bodies used for irrigation, unable to return to the river. This is a particular concern for young fish (eggs, larvae and juveniles), and particularly species such as Murray Cod, Golden Perch, Silver Perch and Trout Cod, which drift downstream as larvae after hatching, making them particularly vulnerable. Their drifting phase also coincides with peak irrigation periods (November and December).

Hydropower impacts:

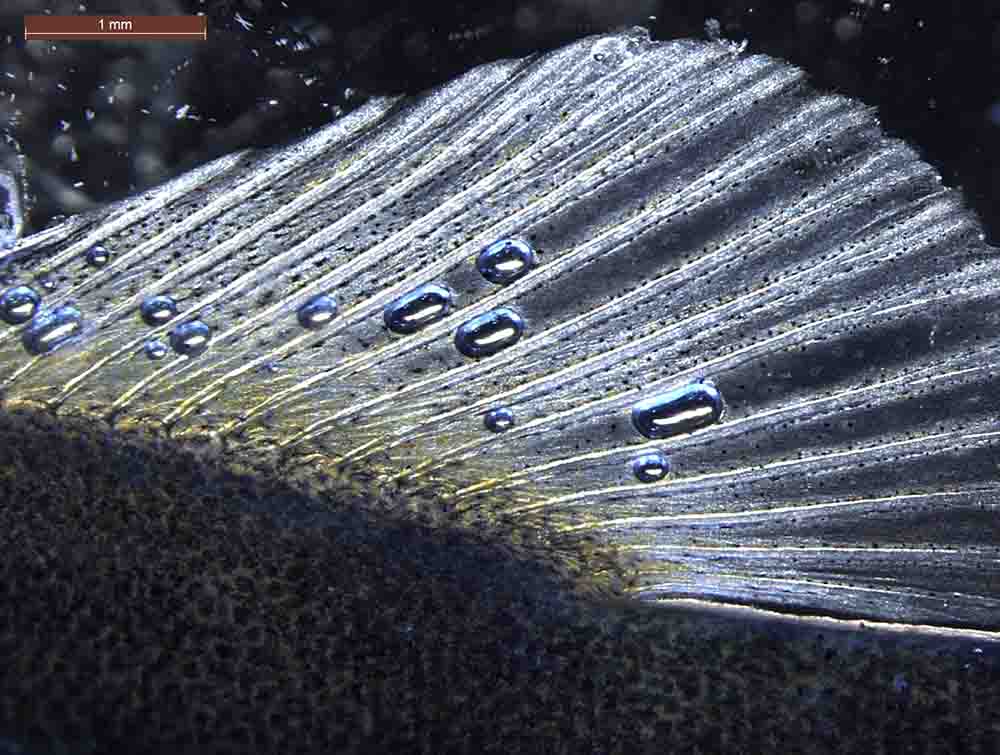

Another emerging threat for fish moving downstream is hydropower facilities, which use water flow to turn large turbines, generating energy in the process. Unfortunately overseas examples are highlighting that these hydro facilities can seriously impact on fish travelling downstream, exposing them to dramatic changes in pressure (the equivalent of travelling from sea level to the top of Mount Everest in less than one second), risk of injury from hitting turbine blades or other solid components as fish are swept downstream, and exposure to violent shearing conditions when water rapidly changes speed or direction.

On the Columbia River approximately US$7 Billion has been spent attempting to prevent loss of migrating salmon in the region, however the impact of hydropower infrastructure on downstream-migrating fish has resulted in an ongoing reliance on hatcheries to bolster flagging populations. As both State and Federal Governments in Australia attempt to tackle climate change and meet their own renewable energy targets, hydropower is again being explored as a potential component of the future ‘green’ energy mix throughout Australia.

Barotrauma injuries such as this air bubble within a 22 day-old Murray cod (above) and these bubbles in the dorsal fin of a 65 day old Murray cod (below) can result from rapid decompression experienced whilst passing through undershot weirs, or hydropower facilities, and can result in mortality. Photo credit: Craig Boys

There is no doubt that many of our freshwater fish species are not doing too well; of the 46 native fish species in the Murray-Darling Basin, 26 (over half) are now listed as threatened under state or commonwealth legislation. Researchers have recorded larval Murray Cod from the lower Murray-Darling Basin during surveys (confirming spawning is occurring), but have failed to find one year old fish for the last 15-20 years. Where are these larvae disappearing to? Could our water infrastructure be contributing to this problem? It is generally accepted that the biggest losses have coincided with the rapid growth of water resource development and river regulation over the past century.

Whilst discussing these issues with Dr Boys he made the point

“when you consider how much is spent annually on stocking programs, instream rehabilitation and the purchase of environmental water throughout Australia to support Australia’s valuable recreational fisheries, it seems crazy that we continue to allow such large volumes of wild fish to be injured, killed and extracted needlessly every year. But the ray of light is that in most cases, there are practical solutions, which have proven effective elsewhere in the world, but have yet to be applied within Australia”.

The irrigation sector has been proactive in working with NSW DPI researchers to establish the first design criteria for fish screens at water diversions within the Murray-Darling Basin. But unfortunately, although in a position to start rolling out a pilot screening projects, there is currently no coordinated screening program or funding scheme to assist irrigators upgrade their diversions.

Fisheries managers are already working with river operators to promote the use of more conventional top spilling weir design (which are far less damaging to fish), rather than continuing with the construction of undershot weir designs. Research is also underway to determine the hydraulic conditions most conducive to fish survival at river infrastructure, with the view of designing more ‘fish-friendly’ options. A few facts to finish up with:

- Many species of native fish, including Murray cod, Golden perch and Trout cod, drift downstream during their early life stages. They also undertake repeated downstream movements throughout their lives. This behaviour makes them vulnerable to injury or death when passing weirs, dams and irrigation diversions.

- Millions of larvae have been retrieved from individual irrigation canals and huge numbers (as many as 95%) of larvae can be killed when they pass downstream through weirs.

- There is currently no coordinated and funded screening program to prevent the loss of fish at water diversions in Australia, despite the fact that programs in North America have been hugely successful for close to a century.

- NSW DPI researchers are currently using state-of-the-art barometric chambers and swimming flumes to determine the hydraulic conditions required at dams, weirs and hydropower facilities to ensure the safe downstream passage of native fish.

Related stories:

https://finterest.com.au/how-and-why-people-change-the-flow-of-water-understanding-natural-vs-regulated-flows/

Queensland’s Dewfish Reach installs irrigation screens to save our native fish