Native fish in the Murray-Darling Basin (MDB) have adapted to ‘boom and bust’ cycles of water availability and flow. Over the last century and a half, however, we have substantially altered the magnitude, frequency and seasonality of water flows in many river systems. These changes affect all aspects of a fish’s life, and are one of the main reasons native fish have declined in the MDB.

Every creature has particular habitat, food and life cycle needs which have evolved over millennia. It is easy to understand why Polar bears can’t survive in the Australian desert – it’s too hot and there aren’t enough seals to eat. It is also clear why Numbats wouldn’t survive in Antarctica – it’s cold down there and termites are hard to come by!

It’s the same for fish – they won’t survive if their habitat, food and life-cycle requirements are not met. Water is necessary, but there are many other ingredients which are required to support a fish’s needs. Let’s delve a little deeper into some of these fishy requirements for those species that call the MDB home.

Habitat:

Habitat for fish consists of the type of waterbody it lives in (e.g. lakes, wetlands or rivers), the hydrology of the waterbody (flow, depth, seasonal water availability etc.), physical structures like logs or plants and, what we loosely refer to as water quality. These habitat elements differ widely between fish species.

Some fish (such as Golden perch) prefer to live in flowing steams where flow pulses are generally required to generate a spawning response, with some individuals migrating over 1000km upstream to breed. Their eggs and larvae also benefit from flowing water which carries them downstream enabling wider dispersal. In contrast, Southern pygmy perch avoid flowing water, preferring still pools or wetlands with lots of aquatic plants, in which they complete their life cycle.

Physical structure within waterbodies can also be important for survival. Snags in flowing rivers create sheltered nests in which Murray cod often lay their eggs. The flow outside their sheltered nests brings a supply of food from upstream to hungry parents, and transports zooplankton for their offspring to eat. Aquatic plants in wetlands and lakes provide food-rich shelter in which Murray-Darling Rainbow fish hide from predators (birds and bigger fish), and a substrate on which they lay sticky eggs.

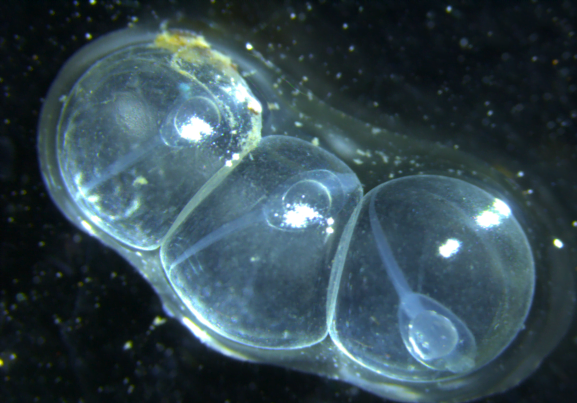

The quality of the water and the way it interacts with the environment are also very important to fish. Spangled perch live in the warm water typical in the north of the MDB. They occasionally venture into the Southern MDB during big floods (i.e. the Murray River system), but are unable to survive the cooler winter water temperatures in the south. At the other extreme, Barred galaxias are adapted for life in cooler mountain streams, and cannot survive warmer summer temperatures in lowland rivers. Barred galaxias (see image at top of page) habitat needs to be low in salinity, while the Murray hardyhead actually prefers salty habitats like floodplain lakes, with some populations recorded in wetlands with saline levels more than double sea water.

Altering parameters like temperature, salinity and dissolved oxygen (which fish absorb by ‘breathing’ through their gills) changes these habitat elements and can be detrimental to fish. Blackwater events are often accompanied by depletion of dissolved oxygen which can result in fish deaths – particularly bigger fish which have higher oxygen demands. Clearing of riparian vegetation or intense grazing along river banks can cause high sediment run off which, in turn, reduces water clarity. Not only do these sediments smother plants and fish nesting sites, they also reduce light penetration, effecting dissolved oxygen production by aquatic photosynthesisers.

Life-cycles:

Each fish species in the MDB has a preference for where and how it breeds. Some lay eggs in a nest, others broadcast thousands of egg into river flows. Most native fish species synchronise their breeding to occur in warmer months. This is not a coincidence, but a strategy that has evolved over thousands of years. It makes sense to produce offspring at this time of year when there is likely to be more resources available to support survival, and flow to aid dispersal.

Unsurprisingly, changes to habitats or flow patterns impact on fish life cycles. Reduced flooding isolates wetland habitat needed by floodplain fish like Murray hardyhead. Cold water releases from the depths of reservoirs behind large dams in spring can disrupt the development of tiny Murray cod in their nests.. Removing snags and flow variability reduces the ‘patchiness’ of habitats in a waterbody, reducing its suitability to a variety of fish.

Connectivity, which facilitates movement between habitats, is also important for the completion of life cycles. Longitudinal connectivity along the length of the river or between catchments may be critical for completion of life cycles by species that occupy a range of habitats over vast areas (e.g. Golden perch). Lateral connectivity between rivers and their floodplain is equally important in providing access to non-flowing wetlands that are critical for other species like Southern pygmy perch.

Food:

Fish also need a reliable food supply. Historically, natural flow cycles in the MDB promoted diverse aquatic food webs which, in turn, supported healthy fish communities. Without natural flow variability, nutrients and resources become depleted and food webs are compromised. This is akin to deforestation; where clearing of vegetation reduces a mosaic of terrestrial habitats to broad areas of homogenous habitat.

Using the right recipe:

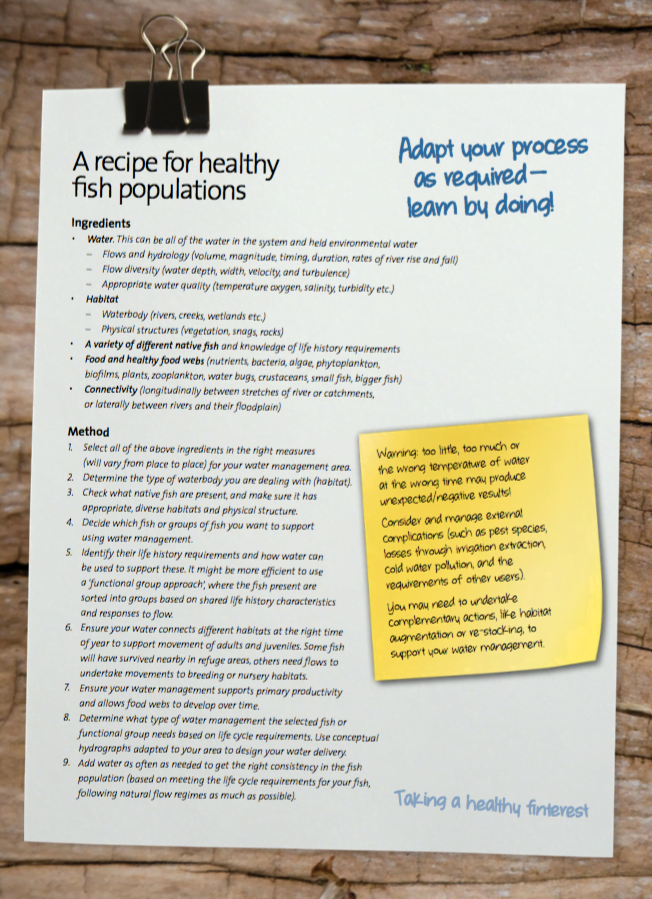

This diversity of habitat, food and life cycle needs means that a wide range of aquatic environments and flow regimes is necessary to support the range of fish species found throughout the MDB. Environmental flows provides us with the opportunity to try and meet these needs – but there is more to the recipe than just applying water.

A simple way to think about managing water to achieve everything fish require is to compare it with making a cake. You need all the right ingredients. Water is the most fundamental for fish, but remember it has to be the right salinity, temperature, clarity and so on. You also need snags, plants and….oh wait, don’t forget you also need the fish themselves and a good understanding of their life cycle needs. For some species which are particularly rare nowadays, we may even need to consider reloaction of fish from places where they still persist naturally – or from captive breeding programs – back into former habitats from which they have disappeared.

Finally, you need to combine these ingredients in the right order, use the right utensils (i.e. appropriate waterbody) bake your cake at the right temperature, for the right amount of time and then dress it for service. We can use our understanding of fish needs to enhance productivity and support healthy fish communities. To get it right, we just need to ensure we combine all the essential elements correctly – the ingredients, method and utensils!

We are now using this ‘recipe’ to guide us as we make decisions about environmental flows for fish.

A pdf version of this story is also available to download here. For more great stories like it, you can purchase or download a copy of RipRap 39 magazine

Related stories:

Environmental flows – connecting hydrology and freshwater biodiversity